A Radical Behind the Lens

Legendary Argentine filmmaker Fernando Birri, a friend of Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Fidel Castro, is a visiting professor this semester

By Marjorie Howard

Argentine filmmaker Fernando Birri is talking about his art: when he chooses to be solitary, he paints or writes poems. When he prefers to collaborate, he makes films. And, he adds, with a mischievous grin, “I can also cook and dance.” Sitting at a table in a small auditorium at the Olin Center, he taps his feet in rapid steps.

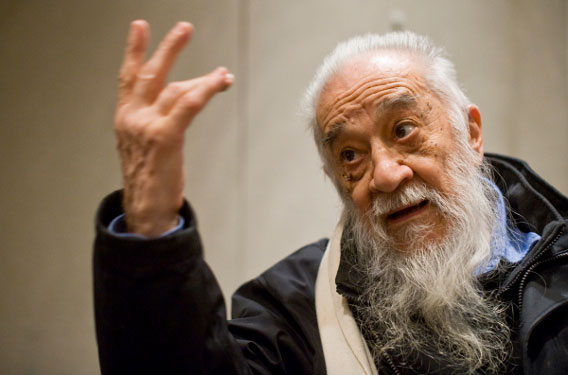

“Do you know what real old age is? It’s the loss of awe. When one is no longer capable to dream with his eyes open, he’s an old man,” says Fernando Birri. Photo: Alonso Nichols

Birri, who is a visiting professor in the Department of Romance Languages, is considered a founder of the New Latin American Cinema movement, which began in the 1950s in Argentina. It sought to raise consciousness in Latin America about political and economic issues. Still sporting his trademark long beard, now turned white, and donning owl-like glasses for reading, Birri has lost none of the passion, curiosity and sly humor of his youth.

This fall he has been teaching workshops on Latin American film and on filmmaking, bringing to his students the vast experience of a man who has lived in several countries, befriended both Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Fidel Castro, founded two film schools and made movies that changed the way Latin Americans think about the cinema.

“His early films have inspired generations of filmmakers concerned with social and political issues all over Latin America,” says José Antonio Mazzotti, the professor of Latin American literature in the School of Arts and Sciences who invited Birri to Tufts. “Since Birri, Latin American film has become not only a form of entertainment, but also a tool to think about the subcontinent reality with an eye for social change.”

From Puppeteer to Filmmaker

As a child, Birri put on puppet shows for neighborhood children, and he still considers himself a puppeteer. As a young man, however, he wanted to reach as large an audience as possible, so he studied theater and later, in Rome, filmmaking, becoming an assistant to Italian director Vittorio De Sica, known for portraying realism in his films.

Watch an excerpt of Tire Die (Toss Me a Dime), Fernando Birri’s first feature film, in the original Spanish version.

He returned home in 1956 and founded the Film Institute at the Universidad Nacional del Litoral. He began making his own movies, befriending a young writer with whom he later started a film school in Cuba, with the blessing of Castro. The young man was Garcia Márquez, the Nobel Prize-winning author. Are they still friends? “No,” says Birri, pausing for effect. “We are brothers.”

“Look,” he says, explaining their connection in Spanish through interpreter Anne Cantu, a lecturer in the Department of Romance Languages. “If I had to write short stories and novels and things I haven’t written, I think I would have written like he did. But so it won’t sound like false modesty, if Marquez had been a filmmaker, which he wasn’t, I think he would have made films like I did.”

Birri’s first film, Tire Die (Toss Me a Dime), was a documentary released in 1960 about the lives of impoverished children who would wait for trains outside Santa Fe, Argentina. They would yell to the passengers for money and chase the trains, sometimes perilously, as they went over a bridge. His 1961 film Los Inundados (The Flooded Ones), which won an award at the Venice Film Festival, was about a poor family forced to take multiple train rides during floods in order to reach safety. In 1985, he made a movie called Mi hijo el Che (My Son, Che), about the revolutionary Che Guevara.

An Abundance of Possibilities

In one of his workshops at Tufts, Birri teaches students about Latin American cinema; in the other, he is teaching them how to make a film. The topic for the student films is migration, a subject Birri uses to address cultural change. He’s fascinated by how people make the transition from their native culture to a new one and how that new culture influences them.

What he’s trying to give his students, he says, “is some kind of a key or code with which to observe reality and a method to be able to express that reality in cinema.” He pauses. “Maybe there’s a third thing: courage—the courage to attempt things, to not be inhibited by the fear of making a mistake.”

Mazzotti says Birri’s students admire him not only for his films but for his teaching. “One of his students gave him the best compliment a teacher can receive. She said that Professor Birri was the only professor who has taught her how to imagine and to create rather than to repeat information.”

As it happens, Birri holds Tufts students in high esteem as well: he finds them to be “very serious and responsible and very young.” Coming from him, that’s the ultimate praise. “Youth is not just a question of biology,” he says. “Do you know what real old age is? It’s the loss of awe. When one is no longer capable to dream with his eyes open, he’s an old man.”

And his advice to the would-be filmmakers? “See everything you can possibly see, because the audiovisual universe in these times has such an abundance of possibilities that 50 years ago would have been unimaginable.”

Marjorie Howard can be reached at marjorie.howard@tufts.edu.