Found in Translation

Exploring the connection between Japanese literary hipster Haruki Murakami and writer Raymond Carver

By Helene Ragovin

Among the most popular courses taught by Hosea Hirata, a professor of Japanese, are those dealing with Haruki Murakami’s novels and short stories. Murakami—a former writer-in-residence at Tufts—is something of a global cultural phenomenon. His tightly crafted, absurdly humorous fiction has earned him rock-star status far beyond his native Japan and has been translated into at least 35 languages, including Estonian, Icelandic, Farsi and Thai.

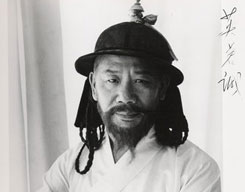

Haruki Murakami “may be talking about Japan particularly, but it doesn’t seem like it is old, exotic, traditional Japan—it’s a very contemporary, postmodern, metropolitan place,” says Hosea Hirata. Photo: Melody Ko

Murakami is also a prolific translator in his own right. Along with bringing selected works by American writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Irving and J.D. Salinger into Japanese, he has also translated the entire oeuvre of short-story writer and poet Raymond Carver, a task he set for himself more than 20 years ago.

Among contemporary Japanese writers, Murakami is arguably the most “American” in style. Among his influences are Fitzgerald, Richard Brautigan, Kurt Vonnegut—and Carver, known for his stark, minimalist technique and tightly structured stories. This past summer, Hirata taught a course at Tufts that set Murakami and Carver side by side; students read and analyzed the short stories of each writer.

Hirata’s acquaintance with Murakami goes beyond the printed page—the two were colleagues at Princeton in the early ’90s. At the time, Murakami was writing the novel that would become his masterpiece, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle.

Tufts Journal: What gave you the idea for this class, comparing the short stories of Murakami and Carver?

The link between Haruki Murakami and Raymond Carver is that in 1982, I believe, Haruki read a story by Raymond Carver, So Much Water So Close To Home. And he was very moved and wanted to translate Raymond Carver into Japanese, and soon he was convinced he wanted to translate everything Raymond Carver ever wrote. About four years ago, he finally finished, and published the complete works of Raymond Carver in Japanese. So that is the connection.

When I thought about this class, I thought it would be very interesting to read the short stories of Carver side by side with Haruki’s short stories, which are receiving world acclaim.

Of course, Raymond Carver never read Haruki’s work. [Carver died of cancer in 1988; Murakami’s first novel to be published in English outside Japan, A Wild Sheep Chase, did not appear in translation until 1989.] But they did meet once, and Haruki became quite friendly with Tess Gallagher, Carver’s widow, after Carver died. They corresponded frequently, and Tess really entrusted Carver’s entire manuscripts to Haruki, so he could translate everything.

There are many stylistic similarities in Murakami’s and Carver’s writing. But they have very different biographies.

What is very interesting is that Raymond Carver went through a very difficult life. He was almost killed by being an alcoholic, and he almost destroyed everything. Haruki, on other hand, is a devoted health nut. They came from very different backgrounds. Haruki’s parents were teachers; he was surrounded by books as he was growing up. Raymond Carver came from a blue-collar family; he went through a difficult marriage. Their backgrounds are so starkly different. I think Haruki was attracted by something that he is not.

What about the students’ reactions to the two authors?

It’s interesting. Some of the students came because of the work of Haruki Murakami and some because of the work of Raymond Carver. I don’t think there was anybody who knew both writers well enough. The contrast between those two writers is quite great, and at the same time, there are similar themes; similar use of props—the telephone, for example. Raymond Carver was not influenced by Murakami, because he never read his work, but Haruki Murakami started reading Raymond Carver at an early stage in his writing career, so that unconsciously, certain things might have crept into his work through reading and translating Raymond Carver.

Murakami has lived in both the U.S. and Europe for large stretches of time to avoid the attention that comes with celebrity. But his appearances still cause a stir, such as when he gave a public reading at MIT in 2005.

MIT advertised it as a public event. I got there about a half hour before the lecture started; it was a mob scene. I’d say there were over 1,000 people surrounding that hall. Some girls were crying because they couldn’t get in. Some people were complaining that they’d flown in from Cincinnati especially for this. I’d never seen anything like this for a reading by a novelist from a foreign country. Incredible! He attracts all sorts of people: old, young, men, women.

Murakami has received the Franz Kafka Award from the Czech Republic. He’s widely read in Russia and China; he has a sizeable following in South Korea, particularly among “thirtysomethings.” Why does his work transcend geographical and cultural boundaries?

That’s really the main question I always ask my students. One thing is that Haruki’s work is always easy to read, deceptively so. Another thing is that he’s often funny, very comical. He often writes about young people, so young people can really identify with the characters he writes about. Another interesting thing is he often uses very surreal or fantastical characters or realms or happenings—magical realism.

And he is really focused on contemporary culture, which appears to be almost borderless—sort of a metropolitan kind of culture. He may be talking about Japan particularly, but it doesn’t seem like it is old, exotic, traditional Japan; it’s a very contemporary, postmodern, metropolitan place.

Helene Ragovin can be reached at helene.ragovin@tufts.edu.