Backstage at the Revolution

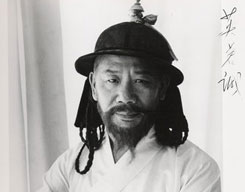

A new book about Chinese actor Ying Ruocheng’s life—from prisoner to politician—offers a rare view inside his country’s struggles in the last century

By Taylor McNeil

Chinese actor Ying Ruocheng was at home in Beijing with his wife and several friends on April 28, 1968, knocking back a few drinks and eating conchs, when the doorbell rang. Two smiling strangers asked him to walk around the corner to the local police station to “verify a few points.” Soon they bundled him into a waiting car, with only the shirt on his back and 27 cents in his pocket, and led him to a prison cell crammed with 19 other men, the smell of fear palpable.

Click the play button for a slide show narrated by Claire Conceison, who talks about the life and times of Chinese actor Ying Ruocheng and the book they collaborated on.

It was the middle of the Cultural Revolution, when China was gripped by political witch hunts. But Ying quickly made up his mind: he was not guilty of anything, and he was not going to be fearful or despondent. A survivor, he secretly collected paper and ink and kept a notebook during his time in captivity. In it, he recorded useful skills he learned by talking with other inmates—everything from mixing cement to pickling peppers, talents he put to use in his three years in prison and labor camp.

Remarkably, some 18 years later he was named China’s vice minister of culture, having in the meantime translated and starred in a Beijing production of Death of a Salesman, directed by playwright Arthur Miller.

When Claire Conceison, an associate professor in the department of drama and dance, first met Ying in Beijing in 1991, she was captivated by his story. Now, as a result of their subsequent collaboration, Ying’s autobiography, Voices Carry: Behind Bars and Backstage During China’s Revolution and Reform, has just been published by Rowman & Littlefield.

An expert on Chinese theater, Conceison happened to be visiting the Beijing People’s Art Theatre with a local friend while Ying was there directing a production of Major Barbara. “I had heard of him,” she says. “He was a very important person in Chinese theater, as an actor, director and translator.”

Ying invited Conceison to sit with him as lighting cues were adjusted, and for the next two hours they talked theater. When they met again by chance a few years later, Conceison was armed with a tape recorder and conducted a short interview with him. It turned out to foreshadow a much larger project. In the mid-1990s, Ying was quite ill, and at Conceison’s urging, decided to tell his story—but with a twist. He was going to do it in English, and with Conceison.

Ying, who was born in 1929 and educated at missionary schools, learned English at age 12. Prior to meeting Conceison, he had started writing in English about his arrest and time in prison during the Cultural Revolution, but had shelved the project due to his illness.

Conceison spent a month each summer from 2001 to 2003 meeting with Ying daily, taping their interviews. “He loved the English language, his adopted tongue,” Conceison says. “Part of the pleasure for him was to speak English every day, and to really review his whole life in a language he loved.”

Ying died in 2003, and Conceison was left with more than 100 hours of audio and videotape interviews. She edited and carefully annotated the transcripts, creating what she calls a collaborative autobiography, as “neither invisible ghostwriter nor full coauthor.”

A Window on China’s History

Ying’s autobiography captures the dizzying pace of change in China during his lifetime, from arranged marriages and bound feet to civil war and revolution and the opening to the West. He begins with his arrest and imprisonment in 1968, but then fills in his family’s back story.

He tells about his Manchu grandparents, who worked their way into the cultural elite in Qing Dynasty China; his father, a university president who was taken to Taiwan by the Nationalists in 1949, never to be seen by his family again; and his children, one of whom is a successful television producer and film actor in China today.

But what really sticks with the reader is a sense of Ying himself. He was a brash youngster, tossed out of various schools until he landed at Qinghua University. He was an actor who used his English skills to become an accomplished translator. And he was a man about the world, who traveled abroad for the first time in his 50s, became close with Arthur Miller and starred in Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 film The Last Emperor.

The result is “a completely new vantage point from which to view 20th-century China,” says Jonathan Spence, the Sterling Professor of History at Yale University and a leading China scholar.

Voices Carry is currently being translated into Chinese—a somewhat ironic turn of events given it’s the autobiography of a Chinese actor. And tellingly, it won’t be a complete version. The Chinese Ministry of Propaganda censors everything published in the country, and so perhaps Ying was right to tell his story in his adopted language: it’s the one that allows him to truly tell the full tale.

“My wish is that, even to a small extent, the reader can experience what I and others who met Ying experienced, sitting beside him having a conversation,” Conceison says. “I want people to feel his presence, to experience the charisma, the personality, the vibe, the wit of this extraordinary man.”

Taylor McNeil can be reached at taylor.mcneil@tufts.edu.