The Secret Language of Music

Mary Talusan explores the subtle communication of talking gongs – and now guitars – heard in the southern Philippines for centuries, and makes them her own

By Marjorie Howard

Music is everywhere in some villages in the southern Philippines: shimmering gongs ring out special sounds for celebrations, ceremonies and rituals. The gongs also serve as a way for people to talk to each other, with musical phrases communicating words and sentences, even allowing young men and women to court each other.

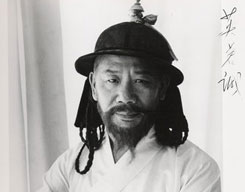

Mary Talusan learned to play the kulintang, gong music from the southern Philippines, as part of her research, and now performs it, too. Photo: Alonso Nichols

Halfway around the world at the Granoff Family Music Center, Mary Talusan sits at a computer in her office and clicks “play” to start a video. A Filipino man softly hammers out his musical message: “I’m looking for a girl with a beautiful face,” he says, using the subtle language of the gongs to flirt with a young woman.

You’d have had to grow up among the Magindanao people of the Philippines to fully understand the talking gongs, says Talusan, a Mellon Scholar at the Center for the Humanities who studies the music and culture of the country where she was born. On November 23 she will join her friend and mentor, Danongan Kalanduyan, and his company, the Palabuniyan Kulintang Ensemble, on stage at the Tufts Festival of Southeast Asian Music.

The Filipino music is called kulintang, the gong-drum ensemble played by Muslim minority groups in the southern Philippines. Kulintang also refers to the main instrument, a set of eight embossed bronze gongs in graduated sizes and tuning. The gongs sit on a horizontal rack and are played with wooden sticks. Kalanduyan, whom Talusan calls guro, or teacher, is one of only two Muslim Filipino teachers of this tradition in the United States and is considered a master of the art form.

Click on the play button to see the Palabuniyan Kulintang Ensemble in concert.

For Talusan, the study and performance of kulintang is the ideal meshing of her interests. Born in the Philippines, she came to the United States with her family at the age of four after her parents received fellowships at Tufts University School of Medicine. She studied cello as a child, performing with the Greater Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra, and knew she wanted a career in music.

Growing up, though, she became intrigued by stories she heard from an uncle about a group of people in the southern Philippines who managed to keep their own music and culture. They had resisted pressure, not only from Western culture, but from Spanish colonists who had declared all native Filipino culture “evil” and banned indigenous music.

As a graduate student in music composition at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore, she heard Indonesian gong music, called gamelan, and remembers being “completely blown away” by the intricate rhythms and dance. When she learned her country had a similar tradition, she changed her focus.

She went on to earn a doctorate in ethnomusicology at UCLA, where she also learned Tagalog, the native Filipino language. She lived in the Philippines from 1999 to 2000, while on a Fulbright fellowship doing field research in a Magindanao community and studying the language, culture and music of her native country. She has returned several times since, most recently in August with the help of Mellon research funds.

Marching to a Different Drummer

The Magindanao are Muslims from the southern island of Mindanao. In traditional Muslim society, says Talusan, men and women of marriage age are not allowed to speak to each other. Because of this ban, “they learned to talk through gongs. What they’re doing is kind of mimicking their language in their music,” she says.

“It’s almost a way of interviewing potential husbands,” Talusan says. “The guys come and take turns on other instruments, and the woman talks to them by playing an instrument. A man might say, ‘I’m interested in you,’ and she can respond, musically. It’s socially acceptable. The parents are sitting there, and relatives are all around.”

Though talking gongs are a tradition going back centuries, a newer form of music called dayunday, which is played on a three-stringed guitar, sprang up when the Philippines was under martial law in the 1970s and 1980s. It sounds nothing like Western guitar music, but instead mimics a Southeast Asian lute called the kudyapi.

Dayunday, explains Talusan, is an improvised stage drama in which performers of the opposite sex sing about love and desire. The actors take turns singing improvised lyrics and accompanying themselves on the guitar. The show usually depicts two men competing over the hand of a woman, something audiences especially enjoy because the men jokingly insult each other and engage in slapstick comedy.

Click the play button to see a video of a dayunday guitar performance recorded by Mary Talusan in the Philippines.

Talusan clicks on another video. In this one, a woman sits between two men, each playing a guitar. Not a word is spoken as the music continues. Suddenly the woman shyly covers her mouth in feigned embarrassment and the audience murmurs. One of the men, using musical phrases rather than words, has played an off-color limerick, something the audience immediately understands, even though not a word has been spoken.

He goes on speaking through his music, taunting the other suitor by insulting him and emphasizing his own positive traits. Talusan translates: “I’m young and better looking. I’ll take care of you; that guy cannot feed you. You’ll go hungry.”

Talusan is currently working on a book, Women’s Courtship Voices: Music and Gender in the Muslim Philippines, exploring an aspect of society that she believes has been ignored. Customarily, a man tells his family he wants to marry a woman, and the two families negotiate a dowry.

“What has really been elusive,” she says, “is how women feel about the courtship and marriage.” Studying music and what it means to the people who perform and listen to it is a profound experience, Talusan says. “The music is beautiful, and the people of the southern Philippines, who kept their traditions, are fascinating.”

Talusan learned the music the hard way. When she was in the Philippines about eight years ago, she studied kulintang with a niece of Kalanduyan. It’s an oral teaching that Talusan, trained to learn music from written notation, had a hard time with. “I spent many hours of frustration trying to manage the melody and complex rhythms, but I’ll never forget how to play these pieces,” she says.

By learning the music orally, she adds, “I was better prepared to improvise, which is the most important feature of playing kulintang.”

She has played in various venues in the U.S., and is pleased the music is finding its way into American pop culture. She even recently joined Apl.de.Ap, a Filipino-American member of the group Black Eyed Peas, to record kulintang music for his upcoming solo album. The question for those in the know will be, of course, is there hidden language on that recording?

The Tufts Festival of Southeast Asian Music, sponsored by the department of music, presents music and dance of the Philippines and Cambodia, featuring kulintang, on Sunday, November 23, at 3 p.m. Also part of the festival, the Boston Village Gamelan will perform on Saturday, November 22, at 8 p.m. Both performances are free and will take place in the Granoff Music Center’s Distler Performance Hall.

Marjorie Howard can be reached at Marjorie.howard@tufts.edu.