Just Say No to Free Drug Samples

When doctors hand out doses of the latest medication to patients, they are doing more harm than good, says medical researcher

By Marjorie Howard

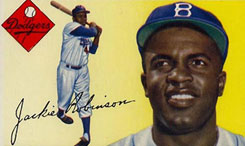

“Who pays for all these free samples that are given out to people who could afford them? The answer is we do,” says Jerome Kassirer. “They are unequivocally a marketing tool.” Photo: Mark Morelli

If your doctor ever offered you a free sample of medicine, you probably took it happily, grateful you didn’t have to fill a prescription and pay for it. But Jerome Kassirer, a professor at the Tufts University School of Medicine, says those samples are nothing more than a marketing tool for the pharmaceutical industry and actually end up costing consumers money.

“Samples are one of the marketing approaches that the pharmaceutical companies use to entice doctors to use their newest and most expensive drugs,” he says.

Kassirer, a former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, says trade organizations representing the pharmaceutical industry claim free samples improve patient care and help millions of financially struggling patients, while at the same time demonstrating new treatments to physicians. Not so, says Kassirer, author of On the Take: How Medicine’s Complicity with Big Business Can Endanger Your Health (Oxford University Press, 2004).

In a paper written with Susan Chimonas of Columbia University and published in the May PLoS Medicine, Kassirer focuses on those ubiquitous packets of medicine that drug companies shower doctors with to the tune of $16 billion a year. Most people think they’re harmless. Instead, says Kassirer, they reach the wrong people and are frequently misused, all the while raising the cost of health care.

Instead of going to people who can’t afford drugs, Kassirer says in an interview, samples go to friends and acquaintances of the physicians or to patients who would have little difficulty paying for them. The most egregious offense, he says, is when physicians sell the samples to make money. But much more common is a doctor who thinks she is simply doing a good deed.

“I went to my ophthalmologist and was getting some new eye drops and she said, ‘Just a minute, I’ll give you some free samples.’ I said to her, ‘Why would you give me free samples? I’m a rich guy.’ She was surprised, because she didn’t expect that I would not accept them. She thought of it as a courtesy. It was very nice of her to do that, but I didn’t think I was the right person to give them to. If you want to give free samples, give them to people who really can’t afford them.”

Even when samples are given to those in need, says Kassirer, they are not necessarily given with the detailed instructions and precautions that come with a prescription. In addition, so-called “starter packs” may be given to low-income people who then don’t have the means to buy medication on their own and are unable to continue the regimen.

Samples are almost never well-tested drugs but instead are the newest agents on the market. “As such,” he and Chimonas write, “they expose patients to risks not yet identified in clinical trials.” Just because a drug is FDA-approved doesn’t mean it’s free of risk, he says. “Many drugs have been approved by the FDA and then been withdrawn from the market when toxicity appeared with prolonged or widespread use.”

Take Vioxx, for example, a drug used to treat arthritis. Kassirer’s paper says that Vioxx became the most widely distributed sample only three years after it was introduced in 1999. Yet by 2005 it was withdrawn from the market because of an excessive risk of heart attacks and strokes.

The prime motivation for samples, says Kassirer, is to influence doctors to prescribe these drugs to their patients. “Who pays for all these free samples that are given out to people who could afford them? The answer is we do, based on the cost of the medications we buy. They are unequivocally a marketing tool. The industry would deny that and they would say they have no influence on physicians, but if they’re spending billions of dollars on free samples, you know they must be spending that money to sell drugs. It’s not charity.”

Kassirer would like to get rid of free samples altogether. Short of that, he says, there are some alternative proposals now getting attention. For example, the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences now recommends that all samples go to a central location in an institution where they could be distributed to people who truly need them, along with information about how to use the medication properly.

Kassirer says pharmaceutical companies maintain doctors won’t learn about new treatments without samples, but he says doctors can use websites and medical newsletters to learn about the drugs. “I don’t think doctors should be relying on industry-supported medical education.”

Free samples don’t have to be a problem. Kassirer points out that many European countries provide universal health care and negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies after formally assessing the benefits and risks of new drugs—and drug companies don’t peddle free samples.

Marjorie Howard can be reached at marjorie.howard@tufts.edu.