Get Defensive

The latest studies show surprising connections between nutrition and immunity, and the experts say there is plenty we can do to stave off illness: exercise, relieve stress and eat healthier

By Julie Flaherty

When cold season rolls around, many sniffle-fearing adults automatically reach for their C tablets, their zinc lozenges and their developed-by-a-school-teacher vitamin and herb concoctions. Yet overall, experts have found little to no evidence that vitamin C prevents or treats the common cold. Studies on using zinc to diminish the severity or duration of cold symptoms are inconclusive. Same goes for Echinacea.

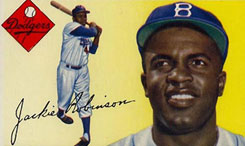

Scientists have known for more than 60 years that a poor diet puts the immune system into freefall. Illustration by Michael Austin

“When I see advertisements on TV calling something an immune booster, I cringe, because most of them, as far as I know, are not based on complete and well-done studies,” says Simin Nikbin Meydani, director of the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA) at Tufts.

That doesn’t mean that nutrition isn’t crucial to your ability to fight illness. Scientists have known for more than 60 years that a poor diet puts the immune system into freefall. That is why diarrhea and pneumonia are life-threatening illnesses in parts of the world where malnutrition is prevalent.

“You need all of the essential nutrients. There is no exception for that,” says Meydani, who also heads the Nutritional Immunology Laboratory at the HNRCA. “Whether it’s lipids, proteins, vitamins, minerals or trace minerals, you need to have them. If you have a deficiency, you can impair the immune response.”

The reason, she says, is that our bodies use specialized cells to fight each of the thousands of pathogens we are exposed to. But if our bodies stocked the number of cells we would need for the job, we would be Costco-sized cell warehouses. “So the way nature dealt with it was to have very few of particular types of immune cells, and when they see a pathogen they recognize, in order to get rid of it, they increase their numbers immediately; they expand and proliferate.” The nutrients we keep in reserve become the building blocks of those antibodies and white blood cells.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

“The question people have been asking is, ‘Does this mean that if I go and take more of these nutrients I will have a better immune response?’ ” As yet, there are no miracle pills, Meydani says, but “there is some evidence that for some nutrients for some age groups that is the case.”

The elderly, for example, may warrant special attention. “When you get older, your immune response does not function as well as a young person’s,” Meydani says. In particular, T-cell mediated function, which fights against viruses, tumors and bacterial infection, slows down.

Germs also appear to turn more aggressive in an older body. While working on her thesis in the Nutritional Immunology Laboratory, Raina L. Gay, N99, N05, and her colleagues conducted a study that showed a benign virus, when put into an old mouse, is more likely to mutate into a virulent form.

“This could be because there is higher oxidative stress in an older host,” Meydani says, referring to the reactive molecules that damage cells. “Or it could be because there are differences in the receptors that allow the virus to enter into the old host and proliferate at a higher rate. When viruses proliferate, the chances of mutation increase.”

To find out if higher doses of vitamins could help older adults maintain their defenses, the immunology lab conducted several studies with Boston-area nursing home residents. They found that when they gave the senior citizens 200 milligram supplements of vitamin E—which is higher than the current Recommended Daily Allowance—they came down with fewer upper respiratory infections, such as colds and sore throats.

The researchers did not see any effect on lower respiratory infections, such as pneumonia. But this could be further evidence that when it comes to supplements, one size does not fit all. When Sarah Belisle, A03, N05, N08, and her colleagues looked at the genetic backgrounds of the nursing home residents who took the vitamin E, she found that the elderly with a certain form of a particular gene did have fewer lower respiratory infections, while those who had a different version were unaffected.

Meydani says the interaction between genes and nutrition could help explain why clinical studies of vitamin E and cardiovascular disease have returned less-than-promising results. In some people, the supplements might work. In their genetic opposites, they might not.

Sometimes Yes, Sometimes No

Tread carefully when it comes to supplements. Fruits and vegetables have phenolic compounds, which can have anti-inflammatory properties, Meydani says, but people should hesitate about taking a whole lot of purified phenolic compounds in supplement form.

“When you have them in fruits and vegetables, you have them in combination with other nutrients, and they could have synergistic or opposing effects with each other,” she says. For example, Harvard scientists found that people who drank five cups of tea a day secreted 10 times more interferon, an immunity marker, than those who drank the same amount of placebo.

But when Dayong Wu, an assistant professor at the Friedman School and a scientist in the Nutritional Immunology Lab, fed catechins, a type of polyphenol extracted from green tea, to laboratory mice, he found it decreased the ability of their T-cells to proliferate.

That doesn’t mean there might not one day be a go-to food for immune system health. Wu and his colleagues have been taking a close look at mushrooms, which have been used as a functional food for thousands of years in Asia, where they are used medicinally to fight tumors. Recent studies have indicated that mushrooms do not directly kill tumors, but may inhibit them by enhancing the immune system.

Wu fed mice a diet containing white button mushroom powder in doses that would translate to two or ten cups of fresh mushrooms per day for a human. The animals showed enhanced activity in their natural killer cells, components of the innate immune system.

“Natural killer cells’ main function is to kill viruses,” Wu says. “They also perform surveillance for malignant cells that could potentially form tumors.”

But before you dig out your mushroom stir-fry recipes, you should know that “there is still a long way to go before we can claim that mushroom consumption can boost the immune function in humans,” Wu says.

In the meantime, here are some science-backed immunity boosters:

Put on Your Sneakers

Several studies have linked moderate exercise with immune function. When your heart gets pumping, it’s easier for your blood to circulate the immune cells that kill off bacteria and viruses. This effect stops a few hours after your gym session ends, but consistent regular exercise seems to have a cumulative effect.

In one set of studies, women who walked briskly for 35 to 45 minutes five days a week reported about half the number of sick days as their sedentary peers. That said, while some exercise is good for fighting germs, very intensive, sustained aerobic exercise is not necessarily better. “Studies have shown that when you do a marathon run, you become more susceptible to infections,” Meydani says.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

Your immune system doesn’t function as well when you are stressed out. Tests on some under-pressure volunteers—including medical and dental students and caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients—found they were more likely to develop colds, were less responsive to vaccines and were slower to heal from wounds than their less-harried counterparts.

Why would this be? The nervous system and the immune system, scientists are finding, interconnect. For example, emotional stress causes the body to release cytokines, the same immune system messengers that initiate an inflammation response against infections. Researchers suspect that when the body churns out high levels of these cytokines over a long period of time, it tunes down the immune response.

On the flip side, calming, meditative exercises, such as tai chi, have been shown to improve immune system activity. Stated positively, “There is a nice mind-body connection when it comes to immune response,” Meydani says. “That is why when college students are studying for final exams, they need to have good nutrition rather than eat junk food.” So much for pulling an all-nighter fueled by a pint of Ben & Jerry’s. Getting a good night’s sleep, by the way, also boosts active killer cells.

Eat Your Fruits and Vegetables

You knew this one was coming. Most any colorful produce will help keep immunity thriving through their carotenoids, vitamins C, B6 and folate. News stories about immunity “superfoods” tend to recommend gorging on specific plants, such as garlic, bell peppers, ginger or pumpkin during the flu season. All are healthful and delicious, but there is no need to play favorites. Variety will not only diversify your nutrient portfolio, it will make you more likely to eat the recommended five to nine servings a day.

Keep Dietary Fat Down

A 2003 Tufts study compared people who ate a typical Western diet (38 percent fat) to those on a cholesterol-lowering diet (28 percent fat) and found the low-fat dieters had better T cell function. The kind of fat may matter, too. While you should definitely limit saturated and trans fat, you might also want to keep an eye on your polyunsaturated fats. A review by Meydani and Wu concluded that a diet very high in omega-3 fatty acids, including fish oil, can suppress immune function.

“It might be good for your heart, but it is not necessarily good for your immune system,” Meydani says, emphasizing that she is talking about excessively high consumption. “When you saturate your cells with a whole lot of unsaturated fatty acids, they are susceptible to oxidation.”

Don’t go to extremes. If you cut your fat intake too much, you might miss out on vegetable oils and nuts, which are good sources of essential vitamin E.

Lose Those Extra Pounds

If looking good in a swimsuit for your beach vacation isn’t incentive enough, losing extra weight can also keep you healthy on the trip. “We’ve done studies with people who are slightly overweight that show when you reduce their caloric intake, you improve their immune response,” Meydani says. Losing even a few pounds can rev up T-cell function. An ongoing caloric restriction study, conducted with Professor Susan Roberts, director of the HNRCA’s Energy Metabolism Laboratory, is yielding similar results and revealing clues about why this might be.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of Tufts Nutrition.

Julie Flaherty can be reached at julie.flaherty@tufts.edu.