The Fuse That Lit the Fire

Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, but his struggle isn’t over yet

By Sol Gittleman

Last January was an auspicious month for the inauguration of an African-American president. Martin Luther King Day fell one day earlier. And there was another birthday on January 31: Jackie Robinson would have turned 90. With the arrival of baseball season, I find myself reflecting on the gains that Robinson single-handedly made for the game, for sports and for racial equality.

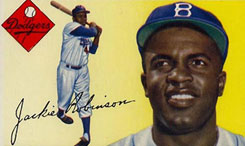

Jackie Robinson, here in a 1955 Topps baseball card, not only transformed baseball racially, he changed the fundamentals of the game.

Pre-Robinson, Major League Baseball was a white preserve. The attitude expressed by Kenesaw Mountain Landis, commissioner since 1920, was typical of the day. “Let them play in their own Negro leagues,” he said—and they did.

But after Landis died, in 1944, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Branch Rickey, felt it was time to make baseball truly an all-American game. After succeeding Landis, Albert “Happy” Chandler, an easy-going Kentucky senator, was asked for his position on blacks in pro ball. He replied: “If they can fight and die on the beaches of Okinawa, they can play in the major leagues.” Rickey’s scouts hit the road.

Everything in Robinson’s life had made him “the right man.” At UCLA, he played six sports in addition to baseball. He went into the Army, and fought segregated busing in Fort Hood, Texas, for which he faced court-martial and won. He was proud of his race, proud of his country and dead set against second-class citizenship. Rickey found him playing for the Kansas City Monarchs, where he was an in-your-face shortstop hell-bent on winning. He was articulate, handsome, happily married and coal-black.

Rickey brought Robinson to Brooklyn and rehearsed the kinds of abuse that the first black baseball player could expect. Then Rickey asked him to promise not to fight back. For this chance, Robinson said he would take what was coming. He signed a contract in 1946 to play with the top Dodgers farm team, in Montreal.

Jackie Robinson’s 1952 Brooklyn Dodgers baseball card, produced by Topps.

Playing second base, Jackie had an MVP season, leading his team to the International League championship. Robinson went to spring training with the Dodgers in 1947 and put on a dazzling exhibition of hitting and running. He was the first Rookie of the Year and by 1949 the Most Valuable Player in the National League. When some of his own teammates refused to play with him, Rickey got rid of them.

Robinson not only transformed baseball racially, he changed the fundamentals of the game. He brought that unique combination of speed, daring and power that produced a more exciting brand of baseball in the Negro leagues than was seen in the majors. Willie Mays, Frank Robinson and Henry Aaron all shocked baseball veterans when they came over from the Negro leagues. They hit home runs, stole bases and played the outfield with an abandon that sent white journalists scurrying to their thesauruses.

Then came Roberto Clemente of the Pittsburgh Pirates, and Latino fans had their first great icon, to be followed by countless others. Having pushed open the door for blacks and dark-skinned Latinos, Robinson lived to see every major league team integrated. As George Will wrote, “Robinson’s first major league game was the most important event in the emancipation of black Americans since the Civil War.” Robinson was, in Will’s words, “the fuse that lit the fire.”

Robinson died in 1972, at 53, ravaged by heart disease and nearly blind, but he still possessed the intensity that changed baseball and America forever. Shortly before his death, he threw out the first ball at a World Series game and spoke his mind: “I’d like to live to see a black manager. I’d like to live to see the day when there’s a black man coaching at third base.” In 1975, Frank Robinson broke down that door; others once outside are still coming in.

But would Robinson be satisfied? What would he say about the shrinking presence of African Americans in professional baseball? Would he point out the irony of a Red Sox spring training roster without a single African American? Racial freedom for him would not have ended with the march at Selma or an Obama election victory. For Jackie Robinson, there was always one more battle to fight.

This article, which is dedicated to the memory of Professor Gerald Gill, was first published in the Spring 2009 issue of Tufts Magazine.

Sol Gittleman is the Alice and Nathan Gantcher University Professor and professor of German, and was provost from 1981 to 2002. His most recent book is Reynolds, Raschi and Lopat: New York’s Big Three and Great Yankee Dynasty of 1949-1953 (McFarland & Co., 2007).