Words into Action

By Gail Bambrick

Changing the way we look at literature can change the world

“A major premise of the book—and my work and teaching—is the usefulness of literature,” says Elizabeth Ammons. Photo: Kelvin Ma

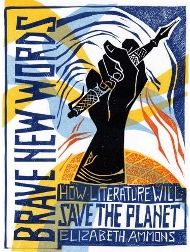

The activist tradition in American literature urges readers to face important social issues and “to take a stand for progressive change,” writes Elizabeth Ammons, the Harriet H. Fay Professor of Literature, in her new book, Brave New Words: How Literature Will Save the Planet (University of Iowa Press).

She calls on teachers and scholars of American literature not to divorce critical thinking from analyzing how to take action. Students, Ammons argues, should be introduced to texts that offer traditions from many cultures and are written by authors who are trying to generate change. “We have to be able to think about all of this together, and be moved by the power of words, the wisdom of history and multicultural perspectives toward action,” she says.

Tufts Journal: What motivated you to write this book?

I felt compelled to because I needed to make a case for the humanities being useful, not simply interesting or enjoyable or provocative. The humanities—and especially literature—are indispensible to solving problems in the contemporary world. But this is not a dominant strain of thinking among professional humanists or in literary criticism right now.

You say some current trends in literary criticism are like “counting angels on the head of a pin.” What is the alternative way to approach texts?

A significant portion of literary criticism over the last 20 to 25 years has become so arcane that it is actually being parodied. This is something to which professional humanists have to pay attention: to whom are we speaking? If we are not making sense to a world of readers and intelligent thinkers, then is it their problem? I don’t think so. There are robust, socially engaged literary critical traditions: feminist, race-based, materialist, indigenous or native studies and eco-critical. All these provide different perspectives that can guide us.

One underlying theme in the book is how we can replace cynicism and nihilism with hope. Can changing the focus of literary criticism and teaching accomplish this?

One underlying theme in the book is how we can replace cynicism and nihilism with hope. Can changing the focus of literary criticism and teaching accomplish this?

While they may not break our bones literally, words are powerful. I think we have a strong sense of how they can do damage. It is important to understand and analyze that. Also, professional humanists are excellent at illuminating buried narratives, multiple levels of language and things going on in texts that may not be totally apparent.

At the same time, we are not as good at recognizing and talking with the culture at large about the power of literature to inspire us, to guide us, to show us the very important values that can lead us to a more just and sustainable future. The activist tradition in American literature calls us to face important social issues and understand them and to take a stand for change. We need answers; we need radical reorientation in our values if we are not going to be the thieves of life on earth.

You say that students want to avoid thinking about the terrible state of the modern world. You write: “But the students are right. The world they are inheriting from us is frightening. We need to tell our students, because it is the truth, that the world could not have looked darker to David Walker or Harriet Beecher Stowe than it does to us today….if [they] did not give in to feelings of powerlessness and despair, can we?”

I tried to draw into this book those authors and thinkers who are addressing the issue of despair rather than avoiding it. Many important thinkers point out that the antidote to despair is not optimism, it is action. So hope, as I talk about it in the book, is not about some shallow, sunshiny optimism. It’s really hard to find, hold onto and work from a basis of hope in the contemporary world.

But it was incredibly hard for David Walker, a black abolitionist in 1830, to hope that slavery could ever be eradicated. We can take courage and inspiration and power from people who have come before—and from our contemporaries as well.

One thing literature can teach us, you say, is that we are spiritual beings who can draw on many traditions to understand our connection to the earth, our social relations and our overall sense of self. Why is understanding the spiritual side of our being important?

The first thing is because most people on earth believe that there is a spiritual dimension to human life. Second, we live in a time of dangerous fundamentalist hijacking of spiritual questions. Whether it is Christian, Islamic, Hindu or Jewish, fundamentalists are commandeering the questions and saying they are the only people with correct answers. Humanists who retreat from questions of spirituality, or ignore them, or just dismiss and scorn the way the questions are put, particularly by fundamentalists, do this at their peril.

We must take seriously the answers found in so many literary texts—the liberatory Christianity of a Chicana text like Under the Feet of Jesus, or the eclectic spirituality of Walden, or the Acoma Pueblo understanding of the sacred in the work of the contemporary poet Simon Ortiz—all of these are important if we are going to include everybody in the desperately needed effort to find a better way of human beings living together on the earth.

If you had to choose just four books to teach in a course that reflects your values and new hopes for the humanities, what would they be?

A major premise of the book—and my work and teaching—is the usefulness of literature. Of course, to me it is all useful, whether it is to provide escape, bring joy into lives or just give pleasure. But I am interested in the activist tradition, so I would choose the overarching theme of environmental justice and planetary damage. On that basis my four texts would be these:

Walden. Take us back to a crazy New England white man, Thoreau, who spent a lot of time in a hut in the woods asking what he could learn from the world of plants and animals, the seasons, the water, the rocks. It is a strongly spiritual book, with a strong action message: we need to simplify our lives, we need to stop consuming, we need to slow down. There is so much wisdom that applies to our time.

Under the Feet of Jesus. This is a contemporary novel by Helena Maria Viramontes, looking at migrant farm labor life in the U.S. It is a beautiful and powerful book, showing what it means to be 13 and working in the fields, so that we can sit down at dinner and have fresh broccoli from California any time of year.

Almanac of the Dead. This novel looks at globalization and the interconnection of exploitation—but it’s an alternative discourse to the one we usually get on globalization. Leslie Marmon Silko generously shares her Native American perspective, which demands a radical reorientation of values as we proceed into the future.

Soil Not Oil. Because we live in a wider world, I would choose Vandana Shiva’s recent book, which represents her social activism in India and her ability to speak to global issues. She is eloquent, powerful, fierce and inspiring. In this book, Shiva links the issue of loss of jobs to devastation of the earth and predatory capitalism.

Gail Bambrick can be reached at gail.bambrick@tufts.edu.