Goooooood Morning, Medford

By Michael Blanding

After 100 years in the radio biz, Tufts can claim its share of “firsts”

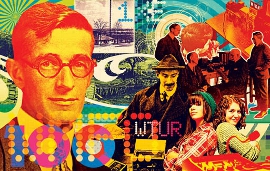

Tufts radioheads: pioneers Vannevar Bush and Harold Power from the Class of 1911 and 2008 DJs Rebecca Goldberg and Rory Clark. Illustration: Seth McCabe

Everyone connected with radio at Tufts has heard of the “train track” incident. In the late 1960s, according to legend, a group of students who worked on Tufts’ AM radio station, WTUR, grew tired of their wimpy 10-watt transmitter, which could barely broadcast to both sides of the Hill.

One night, they ran a coil of wire from their hulking World War II–era navy transmitter in West Hall to the commuter rail tracks behind the building. Suddenly, WTUR’s broadcasts could reach anyone a quarter mile on either side of the train tracks from Philadelphia to Montreal. The FCC was not amused, and swiftly pulled the station’s license. It didn’t open again until 1971, when it took its current name, WMFO.

While it’s a fact that the station was shut down by the feds, there’s no surviving documentation to say why. If the train track story can be believed, however, then Tufts could say for a brief, shining moment, it had the longest range of any college radio station before the advent of the Internet.

That claim is only one in a long line of superlatives in the history of radio at Tufts, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Not only did Tufts’ radio station make the first continuous radio transmission in history. It may well have been the first broadcast station in the country.

It all started in 1910, when Tufts founded its “wireless society”—a year after Guglielmo Marconi and Karl Braun received the Nobel Prize for radio’s invention. By 1915, the club was experimenting with vacuum tubes and crystal receivers to exchange football scores with other colleges by Morse code, says Thomas A. Hart, A68, a former member of the radio club who recently uncovered a trove of documents relating to the early history of radio on campus.

In short order, however, the station met with its first setback—ironically also involving the train tracks behind West Hall. Seeking more range, Tufts radio pioneers erected a 304-foot steel tower on top of the station. “There was a wind storm,” says Hart. “It was a freestanding tower”—no guy wires, in other words—“and it came down.” It crashed onto Boston Avenue and the infamous railroad tracks, says Denis Fermental, associate professor emeritus of electrical engineering, another Tufts radio aficionado. “The thing held up traffic for days,” he says.

A new guyed tower was in place by March 18, 1916, for Tufts radio’s first date with history. Until then, transmissions were made with only intermittent pulses of sound, along with a healthy amount of electromagnetic interference. Transmitting from North Hall, Tufts grad Harold J. Power, E1914, inaugurated a new technology called continuous-wave radio to broadcast three hours of music up to a hundred miles away.

“Before that, radio was mostly dots and dashes,” says Fermental. Under the call sign 1XE, the station continued to broadcast both voice and Morse code messages over the next year. “They might broadcast music and then they’d say, ‘We’ll be right back’ and contact ships at sea,” says Hart.

Revolutionary Entertainment

Radio expanded rapidly at Tufts after Power founded AMRAD (American Radio and Research Corporation), which manufactured radio equipment in what is now Halligan Hall. Its biggest innovation—designed by the former Tufts roommates Vannevar Bush, E1913, G1913, H32 (future Raytheon cofounder and presidential science adviser), and Laurence K. Marshall, A1911 (future chairman of Raytheon), along with the Harvard physicist Charles G. Smith (Raytheon’s other future cofounder)—was a vacuum tube that allowed stations to get rid of bulky batteries.

The Tufts station, its license held by AMRAD, began operating on a daily schedule in 1921, apparently the first station in the country to do so. Several other stations claim regular broadcasts before 1XE—including Pittsburgh’s KDKA, which received the first commercial license. But, as Tufts station operators wrote in a letter to a newspaper at the time, “We were the first to broadcast daily, which is quite a difference.”

Tufts has clear title to the claim of first commercial station in greater Boston, and remained one of the few area broadcasters in the 1920s. The station offered a smorgasbord of programming, including church services, boxing and, on at least one occasion, an address by Boston mayor James Michael Curley.

One of the most beloved programs was a half-hour show during which the “Story Lady,” Eunice Randall, read children’s books. The station played both recorded and live music, including the song stylings of a local act called Hum and Strum.

Even more popular, surprisingly, was a lecture series by Tufts professors. As many as 100,000 listeners tuned in to hear talks on dramatics, athletics, or bridge building. (“What were the alternatives?” asks Hart. “You could go to burlesque or a silent movie, but it was revolutionary to have entertainment in the home.”)

The Depression forced AMRAD out of business, and Tufts’ station went silent in 1929. It came back to life in 1956, when a group of students revived it to broadcast sports, music and news—only to be shut down by the FCC in 1961 (radiation was leaking from the ancient equipment). Next up was WTUR, begun by a group of anti-war students after the Summer of Love in 1967. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds and Cream alternated with debates over the presence of ROTC on campus.

Freeform Radio Comes to Tufts

Watch as WMFO general manager Andy Sayler, E11, talks about how the music makes it to the airwaves. Video: Matt DiGirolamo/Kaitlin Provencher

Radio’s next reincarnation, WMFO, had more staying power: it celebrates its fortieth anniversary next year. From the beginning, the station took on a unique programming style dubbed “freeform.” Most shows featured a mixed fare that careened from, say, Madonna to Mozart or Tupac to the Beatles within one segment. (See sidebar “Freeform Is What We Do” for more on WMFO.)

“One of the things the station pushed really hard is you are not going to come in here and just play your favorite music,” remembers Randolph Williams, E94, a DJ and general manager in the 1990s who is now the station’s FCC compliance officer. “It was supposed to be an educational experience.” That experience included staff acting as both engineers and DJs, as well as students working alongside community members—a Haitian music program run by Medford residents has been a top-rated show for years.

Over the decades, WMFO has launched the radio careers of several alums, including Theda Sandiford, A92, former manager of Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and head of Def Jam’s new media department. “The radio became my whole life while I was at Tufts,” she says.

After a difficult time growing up multiracial in an all-white New York suburb, broadcasting affected her personally as well as professionally. “When I was on the radio, no one could see what I looked like. They heard my words, and as long as I was clever and could connect songs, nothing else mattered. It really became a way for me to bridge the barriers I saw in myself.” One other legacy of her time at ’MFO: her ongoing friendship with George Clinton and Bootsy Collins of Parliament Funkadelic, whom she contacted to propose a 24-hour marathon of their music in 1988.

Today, even as commercial radio struggles in the face of iPods and the Internet, listenership remains strong, according to Andy Sayler, E11, the station’s general manager. “It’s hard for iTunes to compete with a show that plays random music you’ve never heard of, picked out by a real human being for your benefit,” he says.

The station is keeping up technologically, too—gradually converting its tens of thousands of vinyl records and CDs into digital files to augment the nearly 100,000 songs already stored in its digital library. Sayler says the station is currently working on software to recreate the feel of paging through album covers, a step that will let today’s DJs experience the joy of discovery that started with that first music broadcast at Tufts nearly a century ago. WMFO also streams live on the Internet—meaning that for the first time in decades, they’re listening to Tufts radio in Montreal.

Read comments from former DJ Jeffrey Kawalek, A73, about his time at the station, and send your comments to tuftsjournal@tufts.edu.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Tufts Magazine.

Michael Blanding is a Boston-area freelance writer.